The Planning Commission’s gift that could end San Diego’s focus on cars

Our first year of advocacy brought a lot of good news: unanimous commitments from the SANDAG board and the City Council to increase bicycling infrastructure funding, the first ever open streets event in San Diego (CicloSDias), unanimous City Council support for bringing bike share to San Diego, the transformation of a parking lot back into a beautiful public gathering space in the heart of Balboa Park, and more good news and positive focus on bicycling than ever before. But we want to end the year by discussing another huge win that finally opens the door to ending the long-standing practice of allocating road space exclusively to automobiles. This win was the lowered prioritization of Level of Service as a measure of congestion (and by inference, road capacity) on our streets.

What is Level of Service (LOS)? In the context of transportation policy and implementation of facilities for all modes of travel, Streetsblog’s Angie Schmitt writes:

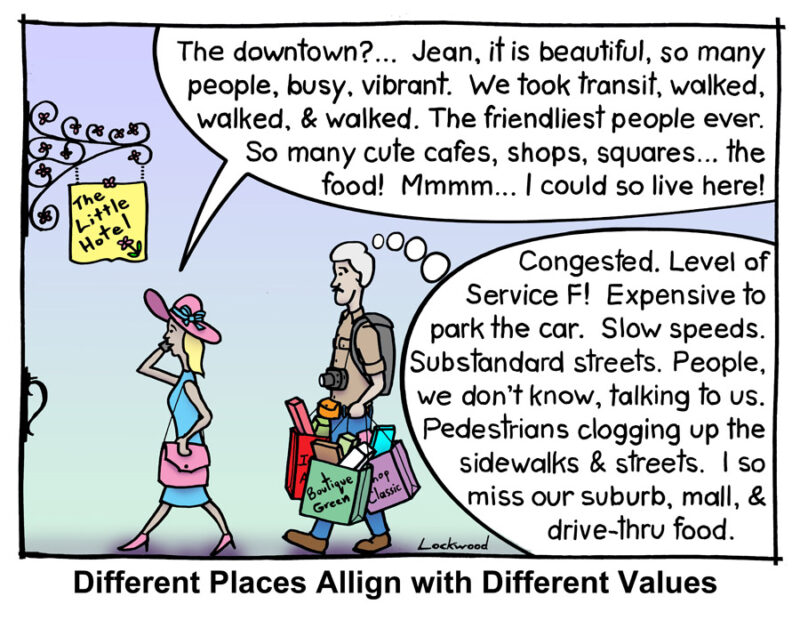

Level of Service, simply put, is a measure of vehicle congestion at intersections. Projects are graded from “A” to “F” based on how much delay drivers experience.

That’s all it measures: the free motion of motor vehicles. And that’s the problem. The safety of people on foot and on bikes doesn’t enter into the equation at all, and transit vehicles carrying dozens of people are subjugated to the movement of private cars. In fact, a high “level of service” generally makes for a much more stressful and dangerous street, since speeding traffic, and the wide lanes that facilitate it, is a leading cause of traffic injuries and deaths.

BikeSD’s first volunteer assistant, Alison Moss, was the first to bring this to our attention about a year ago while she was reviewing and analyzing various policies that govern our street system. Soon, we and Kathleen Ferrier at Walk San Diego began talking to City Council members and their staff. First we met with Mark Kersey’s office (chair of the Infrastructure Sub-Committee), then we met with Lorie Zapf (chair of the Land Use and Housing sub-committee) and then with David Alvarez and his staff, who are experts on the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the state’s landmark environmental act.

What does CEQA have to do with LOS and bicycle infrastructure?

In San Francisco, a lawsuit citing CEQA as an underlying basis was filed to stop San Francisco’s plan to build “34 miles of bike lanes“. If you are scratching your head over that, you are not alone.

As quoted in San Francisco’s Streetsblog, author and planner Jeffrey Tumlin explains,

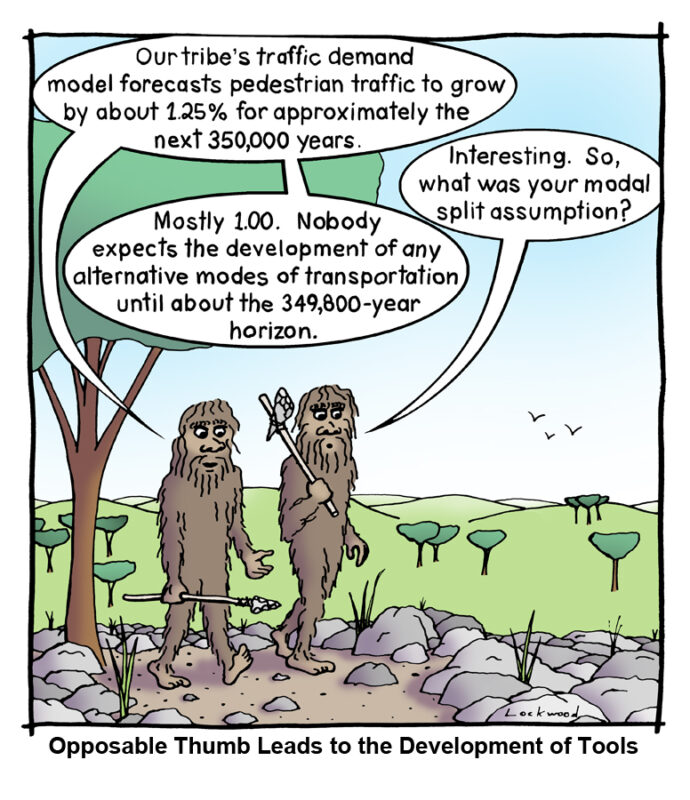

“I’ve been doing transit analyses in California for 20 years,” said Jeffrey Tumlin, principal of Nelson Nygaard, a transportation and land use consulting firm. “In my practice the single greatest promoter of sprawl and the single greatest obstacle to transit oriented development (TOD) and infill development is the transportation analysis conventions under CEQA, the California Environmental Quality Act, LOS.”

In other words, this questionable methodology employed by some licensed professionals has been used to crush or delay accommodation for anything that isn’t an automobile. This would be a useful methodology if the only inhabitants on this planet were automobiles, but we are fleshy human beings that can be killed when struck by vehicles moving on a street with an LOS grade of A, B, or C.

On July 25th, the updated bicycle master plan (approved by city council earlier this month) made its way through review by the city’s Planning Commission. This mayor-appointed body recommends changes in “the city’s General Plan and community plans; makes recommendations on the Capital Improvements Budget, rezonings and related land use matters; and has final approval on subdivisions as well as many permit types”.

Kathleen Ferrier commented at the Planning Commission meeting on July 25th and raised many of the points brought up with council members (as mentioned above) including the conflicting policies that prevent San Diego from facilitating all modes of transportation:

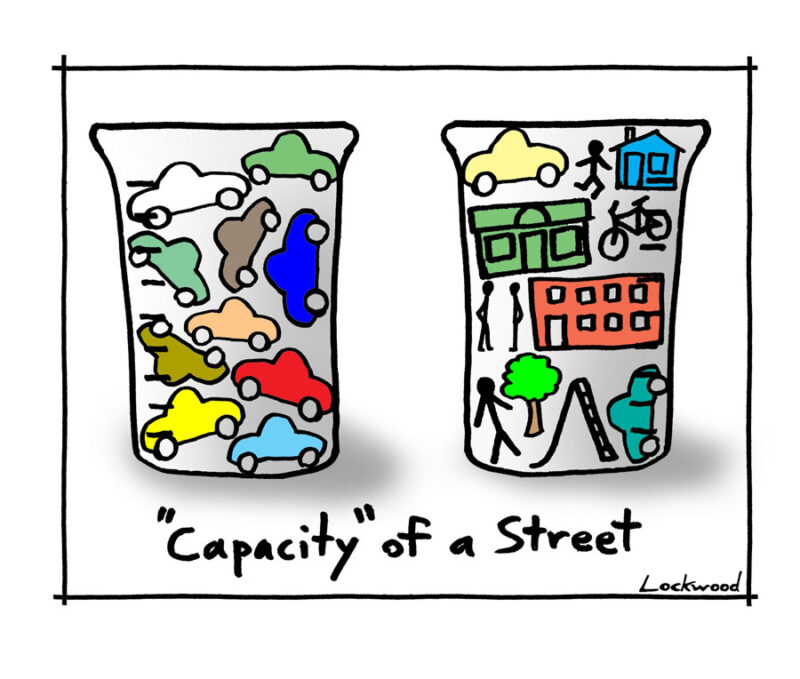

The general plan has many statements about creating multi-modal neighborhoods, great streets, great neighborhoods. But when it comes down to decision-making and how we determine what impacts are, we’re looking at Level of Service still as a city and we know that CEQA doesn’t even require this anymore. It was updated in 2008 to allow cities to establish their own thresholds. San Diego is still behind. Other cities in California are way ahead of us. They are looking at how to redesign or re-institute an LOS policy that considers safety for walking and biking. When we have statements in the EIR that say “bike facilities planned are of concern because they can negatively impact LOS,” I ask that you help us in changing that policy and looking at how we can better balance our transportation decisions, even if it comes to parking, which of course is one of the great challenges we face as we make this shift from a car-oriented society to more safe conditions for walking and biking.

I know biking out there, most days, it is still not safe. It is still worrisome to walk, too. I ask for your support in changing these policies. Thank you.

The Planning Commission Chair, Eric Naslund, immediately grabbed Ferrier’s point and began to question the assembled city staff to clarify the issues underlying the conflicting city policies.

Jeff Szymanski, the city’s Environmental Planner, explained the city’s interpretation of the policies as follows,

The impact was identified because some of these bike lanes have the potential to remove car travel lanes, turn lanes, and so forth. Therefore, from a plan perspective, significant [environmental] impact was identified. Because of the loss of lanes, basically.

The most important thing we learned from this year’s successful advocacy to narrow travel lanes on Montezuma Road was that the city’s wide roads induce high vehicle speeds. This makes bicycling unpleasant and deadly.

Not surprisingly, Szymanski’s response elicited confusion amongst the commissioners. Further discussion revealed that it was policies and guidelines established by the City of San Diego that determine what facilities are being implemented and how.

Another Planning Commissioner, Stephen Haase, picked up the discussion and asserted that he wanted to see San Diego lead on this issue rather than follow other cities on this issue:

I would love to see something done about changing that and exempting intersections and coming up with a multi-modal Level of Service, and I’d like to see us be a leader rather than following the lead on that.

Commissioner Theresa Quiroz also voiced the need to update the archaic Traffic Impact Study Manual (TIS) to include multi-modal transportation.

To date, the TIS remains as the primary guidance document for traffic engineers but there are hints that staff are less afraid to implement a road diet in order to accommodate bicycle riders. The city is scheduled to implement the city’s first road diet in Banker’s Hill next month on 4th and 5th Avenue.

However, action on Haase’s desire for San Diego to be a leader on this issue remains in the air. Earlier this year, state senator Darrell Steinberg was successful in eliminating “traffic congestion and its proxy, Level of Service (LOS), as the focus of CEQA’s transportation analysis“. Steinberg’s bill (which was signed by Governor Brown) ensures that the state’s Office of Planning and Research creates a methodology to replace LOS and a first draft is due in July 2014. Still, it would be nice to see the city’s traffic engineers be proactive about their commitment to multi-modal transportation by eliminating their auto-centric guidelines instead of waiting for the state to do it for them.

—

Much thanks to Howard Blackson, Walter Chambers, Ian Lockwood, Bryan Jones and other progressive traffic engineers, planners, urban designers and Marc Caswell (formerly with the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition) in helping guide our understanding of LOS.